Kimchi Family: C+

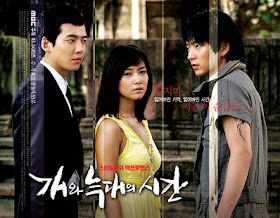

Time between Dog and Wolf: A+

The funny thing about me and “quality" is that I don’t always like it.

The world is positively chock full of undeniably high-quality things that I could happily live without: the works of Ernest Hemingway, the movie Wings of Desire, the vegetable cauliflower. You’re welcome to them…I’ll just be over here reading Twilight while I watch America’s Next Top Model and eat a heaping bowl of Kraft macaroni and cheese. Sure, there’s a time and a place for works of art, but I can be made just as happy by consumable crap with no qualitative merit.

This is why I often take the recommendations of serious critics with a grain of salt. And when it comes to the world of online Kdrama, it’s pretty clear that the webmaster at DramaTic is about as serious and critical as they come—which means I approached the list of best dramas on that site with no slight trepidation. Would a lover of trendy dramas and romantic comedies really enjoy something truly, objectively good? It turns out that the answer is yes, if that thing is number 56 on the list of DramaTic’s best shows of all time: the thrilling, beautifully constructed 2007 drama Time between Dog and Wolf.

I was ready for a change after finishing this year’s saccharine Kimchi Family, and it seemed likely that an action drama beloved by the males of the species would be just the palate cleanser I needed. It turned out that this was true, but not quite in the way I expected: Deep down, under all that fur and fermented shrimp paste, these two shows weren’t so different after all. At heart they’re both about identity and family, and how the two are always inextricably tangled together. (Laughably awful mustaches are also a common theme, regrettably.) With this common DNA, it’s only natural that the dramas faced many of the same decisions—what’s amazing is how different their choices were.

I can see how someone might really like Kimchi Family—at its best, it’s a beautifully produced, big-hearted drama about the power of family and food. I was sold for the first few episodes myself. But what began as a story of foodie magical realism told through the lens of a traditional Korean restaurant and the people who frequent it quickly descended into a series of makjang plot twists taken right out of the Big Book of Kdrama Clichés. Birth secrets? Chaebols in disguise? Gangsters with hearts of gold? Fatal and/or debilitating diseases? Kimchi Family has them all in spades. (In fact, there are at least two separate incidents of each one of these plotlines—and sometimes more.) What it doesn’t have, however, is any true depth, darkness, or hint of friction between its lead characters. Instead of exploring their interactions and motivations, this is a drama that lines up lots of obstacles and stands back—as long as you keep your characters tolerably busy, its writers seem to have decided, nobody will notice that they exist only in one dimension.

As far as I’m concerned, Kimchi Family’s best episodes were the ones that focused on its core group of characters: the Lee sisters and their uncle Kang Do Shik, as well as the two men who became live-in staff members at Heaven, Earth, and Man, their family’s restaurant. The food is beyond toothsome and charmingly presented as the most important part of the Lee family heritage. The girls’ happiest childhood memories involve learning to make kimchi from their mom, and no wonder—she imbues the process with a palpable sense of enchantment, spinning kid-friendly stories about the ingredients of each recipe. When the narrative begins to widen and explore Kimchi Family’s supporting cast, though, the drama loses its focus on creating indelible characters on a meaningful journey, and instead dwells on over-the-top plot developments and overwrought reaction shots.

Kimchi Family is a fine drama for what it is; my problem is that I wanted it to be something more. Its greatest disappointment is a failure to take advantage of its setup. It began with just the right blend of sweet and tart, after all—during the first few episodes, the younger Lee sister is living in the city and working at a fancy French restaurant, having vowed never to return home to be part of the simple, traditional life of Heaven, Earth, and Man. She’s an exasperated perfectionist who wants to succeed in the modern world, and it seems clear that the writers initially planned for her unwilling homecoming to be a fish-out-of-water story. Somewhere around episode 5, however, any development of her character comes to a screeching halt, to be replaced by a series of meaningful smiles over a vat of kimchi ingredients that she shares with her beautiful, childlike sister.

From that point on, the show gives up any hint of being a sophisticated character study in favor of treacly, makjang busyness: A nice-guy gangster searches for his birth father; an orphan avenges himself on those who have wronged him; a man comes to terms with the child he thought he’d lost forever; and a family grapples with the loss of a loved one, all in the space of 24 scenery-chewing episodes.

To its credit, Kimchi Family never fully plunges into cartoon-land, unlike many other making spectacles before it. Its characters resist outright “bad-guy-ness,” and by the final episode most everyone is believably redeemed. In the end, though, Heaven, Earth, and Man has little more to offer than flavorless kimchi primarily composed of

Time between Dog and Wolf, on the other hand, manages to be the best of both worlds: It marries whizbang car chases, hot boys, and gangster intrigue with genuine, keenly felt character insights and a moving story of love and revenge. It’s a delicious fermentation of Alias, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, and the few redeemable aspects of Lee Min Ho’s deeply mediocre City Hunter. Ultimately, this is a show about the push-and-pull that exists between fathers and sons on the road to manhood. It’s about the choice between defining oneself and being defined by another. It’s about doing right when it’s so easy and tempting to do wrong.

Where Kimchi Family succumbed to plot for the sake of plot, the twisty, adrenaline-filled storyline of Time between Dog and Wolf exists not to fill time, but to put the show’s characters through their paces. It twists and turns them, looking at them from every angle imaginable before finally melding them into complete, multi-dimensional wholes.

This drama is peopled not by “good guys” and “bad guys,” but by nuanced, fully drawn characters that sometimes happen to be more good than bad, and other times more bad than good. The ultimate example is Mao Liwarat, the show’s lead gangster and one of its two most powerful father figures. He’s a cold-blooded killer who loves his daughter and carefully mentors his followers, treating them with respect and effortlessly fostering their loyalty. He’s a bad guy, all right, but thanks in part to the measured, weighty performance of Choi Jae Sung, one I wanted redeemed, not dead. (Weirdly, Choi was also in Kimchi Family: he played a distant but cuddly uncle who…wait for it…just happened to be a retired gangster known for his brutality. Did his role in that show predispose me to like him in TbDW? Maybe.)

Although Time Between Dog and Wolf is largely a boy’s club, it also features women—smart women who stand on their own two feet, whether they work at a Korean intelligence agency or quietly wear the pants in a household funded by their gangster husband. Just like their male counterparts, they’re more than I usually dare hope for from a Korean drama.

I can’t say the same for Kimchi Family, even though it seems to be a show geared toward women. Its girls all fulfill traditional roles: they’re teachers and mothers and suppliers of comfort. God help them if they have plans in life beyond docile housewifery, because Kimchi Family certainly won’t—it will instead paint them as cold, cruel abandoners of children who are worthy of forgiveness and nothing more. Also, note that chef in particular is one of the things Kimchi Family don’t allow its women to be. Professional chefs, after all, are men; a woman at the stove is nothing more than a mother. Although Heaven, Earth, and Man is owned by the Lee family, neither daughter has been groomed to take the helm after their father. By the end of TbDW, in contrast, it’s a principled, savvy woman who’s leading the entire intelligence agency.

Time between Dog and Wolf is the exact opposite of Kimchi Family on another front, too. TbDW is beautifully but economically done, with few examples of the hammy overacting (Song Il Gook, I’m talking about you) and baroque direction that characterize pretty much everything about Kimchi Family. In that show, one 10-second reaction shot is never enough: instead, it has to drag out for forty or fifty seconds, giving the actor plenty of time to cycle between four or five different expressions. Its every scene is full of bizarre, unnecessary camera angles: all the zooming and cutting to point-of-view shots from behind random scenery gets distracting after a while. There are even instances when the two halves of a split-screen phone conversation each suffer from multiple, separate cuts and angle changes. (This actually reminded me of a moment in one of the Naked Gun movies when a camera zooms in on an actor, then zooms in some more, and finally zooms in to the point of smacking him in the face. It’s a miracle the cast of Kimchi Family survived, really.)

Instead of feeling self-indulgent and pointless like much of Kimchi Family’s camera work, Time between Dog and Wolf’s direction is calculated to bring the viewer into its characters’ minds: After sustaining a head injury the male lead loses his memory. In the moment he realizes he’s a stranger to himself, there’s a point-of-view shot of the actor looking into a mirrored sun-catcher, which blurs and distorts and replicates his face to the point of unrecognizability, to both him and us. And this is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to meaningful filming techniques—it’s clear that somebody really thought about this show, and worked to film it in the most compelling, appropriate ways.

Then, of course, there’s TbDW’s big finale. It’s one thing to cry at the end of a drama, but it’s another to get goosebumps. An epic shootout staged in a house of mirrors, it’s the show’s final, greatest comment about personal identity and the power of fatherhood.